Alan Morrison

Obituaries

David Nobbs R.I.P.

The Recusant wishes to pay brief tribute to novelist and television writer David Nobbs, who passed away on the 9th August 2015, aged 80. we can think of no better way of paying tribute to Nobbs’ sublime gifts at polemical black comedy fiction than reminiscing a while on perhaps his most acclaimed and certainly greatest achievement, the chronicles of nervously-exhausted middle-management, chalk-striped Surbiton commuter, Reginald Iolanthe Perrin (initials R.I.P.), played by the inimitable, raven-profiled comic character actor, Leonard Rossiter (to this writer’s mind, the Peter Sellers of the small screen).

This writer grew up on such brilliantly written, bittersweet television fare as The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin (1976-79), a series which, in his infant years, rather perplexed and even disturbed him. For Reginald Perrin was no ordinary Seventies sitcom (a la the originally satirical but later more routine and cosy The Good Life), but was, essentially, the chronicling of a middle-class, middle-aged man’s gradual descent into barely contained nervous breakdown and ‘controlled’ disintegration of identity, which leads up to a now legendary ‘faked suicide’ by drowning off the Dorset coast (in seeming homage to Thomas Hardy’s Sgt. Troy, in Far From the Madding Crowd, who also faked his own suicide by drowning off the Dorset coast). The eponymous character also reminded him quite uncannily of his equally nervous father who was commuting from Worthing to London every day on British Rail, replete with trademark pinstriped suit.

Oddly, what used to disturb me the most as a child viewer of Reginald Perrin was the seemingly impenetrable, distant-eyed, almost Stepford Wives-insipidness of his suburban housewife Elizabeth (played by Pauline Yates, who passed away in January this year). Her insouciance strikes a formidable stumbling-block for authentic emotional contact with her husband “Reggie”, and the two continue to drift, almost dream-like, through a suburban existence of mind-numbing routine and ritual (a small glass of Sherry every evening after work before settling down with orange napkins for dinner). Even Reggie’s perpetual lateness arriving at the office every day due to train delays becomes something of an implicit ritual, always “fifteen minutes late” for such gloriously alliterative reasons as “juggernaut jack-knifed at Gerard’s Cross”.

But Elizabeth displays hidden depths of intuitiveness further into the series, particularly during the second, when she knowingly pretends to be mourning her apparently ‘late’ husband, while secretly realising that her new suitor, Martin Wellbourne, a hitherto un-talked about ‘old friend’ of Reggie’s who emigrated to Peru (which triggers an hilarious exchange at Reggie’s ‘wake’: “What’s it like in Venezuela in the winter?” “Peru” “Okay, so what’s it like in Peru in the winter?” “Chilly”) is in fact Reggie returned disguised in a wig, false beard and spray-on tan. Reggie morbidly revels in being a witness at both his own funeral and wake, even if it simply drums home how relatively little he is actually being ‘mourned’, since most of his relatives and old friends appear relatively sanguine, albeit still affectionately nostalgic about him.

The three series of Reginald Perrin are ingeniously thought out: the first, and probably the best in many respects, charts his gradual office-bound decline into mid-life crisis and suicide-faking anomie; the second charts his return, initially incognito, and the birth of his surprisingly successful anti-capitalist shop empire, Grot, which sells completely useless albeit distinctive products (a kind of satire on the built-in obsolescence of capitalist manufacturing); and the third, and perhaps most underrated, charts his last ditch attempt to circumnavigate materialistic existence through a suburban-based commune experiment for the “middle-class, middle-aged and middle-minded” seeking to get out of the ‘rat race’.

In an almost Hardyesque –even Sophoclean– temporal paradox, the circularity of Perrin’s destiny mirrors that of the daily mouse-wheel commute from which he struggles to extricate himself in the first series: his community, the self-effacingly named Perrin’s, is ultimately packed up after too many NIMBYish neighbourhood petitions, and Reggie ends up back in a dead-end office job and once again under the thumb of his original boss (at Sunshine Desserts) –and briefly his own employee at Grot– the dome-headed, gimlet-eyed ‘C.J.’ (revealed only in the original novel as initialling ‘Charles Jefferson’), played supremely by John Barron. C.J. has a fetish for giant cigars and farting chairs for his employees to squirm in as he bears down on them with his inscrutable screwed eyes from his raised altar-like desk, and has passed into popular legend for his indefatigable catchphrase, “I didn’t get where I am today….” (also later used by Nobbs as the title of his own autobiography), which precedes practically every single sentence he utters throughout the three series. The comedy chemistry between Rossiter and Barron as they frequently exchange razor-shop dialogic relay-races throughout the three series is among the most accomplished of any comedy pairing in television history.

But by the end of the series, ‘C.J.’ is himself subordinate to a higher boss, his own older brother, the even gruffer ‘F.J.’, while Reggie is in an inferior managerial position to his days at Sunshine Desserts, and similarly shackled with two excruciating younger executives whose catchphrases are “Smashing”/ “Terrific”.

Reggie ends up, on a particularly sour note to the conclusion of the series, apparently arranging his own more certain suicide on the phone to his new secretary, his last lines –and those of the series– asking for the train times to the Dorset coast before mournfully placing the receiver back on the phone (though Nobbs’ brief revival of the series, the posthumous The Legacy of Reginald Perrin, revealed that Reggie had survived into the 90s, only to be killed by accident when a hoarding advertising the insurance company he was signed up to fell onto his head).

It’s not only the three-dimensional characterisation of the eponymous ‘hero’ which distinguishes Reginald Perrin from any other ‘comedy’ series before or since (it was briefly ‘revived’ with Martin Clunes as a more lugubrious Reggie, and actually was fairly witty in its way, but not a match with the original), or, indeed, the multi-layered ‘journey’ of the narrative, but it’s also the almost neo-Dickensian ‘caricature’-style of the numerous incidental characters (indeed, the likes of C.J. might not have been completely out of place alongside such capitalistic parasites as Pecksniffe and Montague Tigg in Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewitt).

Nobbs had an undeniable genius for blackly comical creations, each with their quirks and personality-type-denoting catchphrases. Elizabeth’s hapless ex-military brother Jimmy (played superbly by hound-jowled Geoffrey Palmer) always starts his lugubrious monologues with “Frankly, bit of a cock up on the catering front…”; C.J.’s two young executives, the neurotic David and smug Tony, punctuate conversations with “Super” and “Great respectively; and even the incidental-incidental characters, such as the verbose Irish drifter Seamus, unlikely business genius employed for his perceived unsuitability to an executive role by Reggie, frequently alludes to his origins as being “from the land of the bogs and the little people”; while lard-faced curmudgeonly self-made Yorkshireman, Thruxton Appleby, constantly harps “If there’s one thing I admire it’s bare-faced cheek”; and psychopathically prickly, incomprehensible Scots Chef, McBlane, periodically complains about “Scrunges”! (Reggie: “How very distressing for you”). But these ‘Nobbsian’ caricatures are more than mere ciphers, just as Dickens’s were: they personify certain social types.

At this juncture the reader may be aware that this writer is genuine fan of Reginald Perrin: on its repeats he caught the series again as an adult, taped it, and since watched the series several times over, in fact, almost ritually every other year, a ‘tradition’ rendered even more enjoyable by the DVD releases, which restored some of the slightly less ‘politically correct’ scenes to one or two later episodes. Ironically, as an adult, he appreciated the wit of the scripting and laughed far more than when he’d detected in it something almost subliminally unsettling as a child viewer.

This writer really could bang on for pages about the multifarious aspects to Reginald Perrin which he’s grown up to admire so much for sheer genius of comic invention and comical polemic (the only comedy series which, in his opinion, comes close to the sheer majesty of Perrin, but for completely different qualities, is John Cleese’s frequently hysterical farce sit-com Fawlty Towers). And he’s no doubt that David Nobbs truly was a writer of ‘genius’ –largely observational genius, but genius nonetheless. Hectic narratives apart, it’s the sheer dialogical gold of the lines and poetically description-rich monologues in Perrin that stands the test of time and greatness (most notably of all perhaps, Reggie’s drunken/drug-induced soliloquy on nihilism at a fruit dessert conference, and his and Jimmy’s relay-race monologues on the social types likely to be alternately attracted to or baited by the latter’s newly conceived “secret army”; “long-haired layabouts… criminals… rapists… papists… papist rapists…” etc.).

This writer uses the term ‘polemical’ very deliberately: for Perrin is nothing if not a gorgeously imaginative comedy polemic on the propensity of so many human beings to live completely in neglect of the imagination; Reggie is an example of a man whose imagination simply cannot be labelled, compartmentalised (excuse the semi-paraphrase from The Prisoner) and put away in a drawer for the daily grind –it has to have its belated vent, and when that begins, there’s no stopping it. Such office-bound polemic on clerical boredom and suited futility has since been tried again, but in more conventional sit-com guise –and perhaps most notably with It Takes A Worried Man (1981-83), written by and starring the talented Peter Tilbury– and none of these have ever bettered Nobbs’ supreme invention.

Reginald Perrin the TV series was of course adapted from David Nobbs’s original –and blacker– novels, The Death of Reginald Perrin (1975, later reissued as The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin), The Return of Reginald Perrin (1977) and The Better World of Reginald Perrin (1978), which this writer has read years ago and for the only time in his reading experience, genuinely laughed out loud throughout all three.

In many ways, in my opinion, Nobbs’s Perrin novels are strongly reminiscent in clipped aphorismic prose style, polemical tone and sublimely figurative depiction of the suburban and mundane, of George Orwell’s early novels, particularly the blackly comical Keep the Aspidistra Flying! (1936), and the more serious Coming Up For Air (1939), in which the middle-aged protagonist, George Bowling, revisits childhood haunts in the village he grew up in, only to find it completely changed; interestingly, there’s a scene in the book when Bowling meets an old girlfriend ‘ravaged by time’, who doesn’t recognise him, while during the second series of Reginald Perrin, Reggie-in-disguise visits an old haunt of his childhood where he meets an old girlfriend serving behind the bar whom he doesn’t recognise).

Had Orwell not lived in such momentous times and been diverted into more serious polemical material, one cannot help thinking that he might well have eventually churned out something even more similar to Nobbs’s Seventies creation. What is certainly clear today is just how prescient, even visionary, Reginald Perrin was, anticipating as it did the rise in bargain-basement and thrift stores selling essentially useless, or at least, worthless, products (Poundland, Poundshop, Poundworld et al), and in its irrepressibly anti-capitalist spirit.

It only remains to say that Nobbs also wrote a number of other significant novels, most of which also became television series and spin-offs: A Bit of a Do (1986),

Pratt of the Argus (1988), and his last book, The Second Life of Sally Mottram (2014), as well as the non-novelised Perrin spin-off (‘Jimmy’’s solo outing), Fairly Secret Army (1984-86).

David Gordon Nobbs, born on 13 March 1935, died 9 August 2015

Educated: Marlborough College and Cambridge University

Alan Morrison © 2015

Gareth Thomas

12 February 1945 in Aberystwyth – 13 April 2016

Welsh television character actor and eponymous star of classic British sci-fi series Blake’s 7, Gareth (Daniel) Thomas, sadly passed away on Wednesday 13th April 2016 aged 71.

Some of this writer’s earliest television memories were of this talented Welsh actor’s portrayal of the dissident figurehead Roj Blake in Terry Nation’s dystopian space opera Blake’s 7 (BBC, 1978-81), even if his regular viewing of this series coincided with the sudden disappearance of the main protagonist for the remaining two seasons dominated by Paul Darrow’s Machiavellian Kerr Avon, but always marked by the mighty absence of Blake. Thomas made two further appearances in the series, in the final episodes of each season, culminating in the climatic and tragic denouement on Gauda Prime in Blake, which saw the near-mythical lost hero return as a seemingly embittered, grizzled and scarred bounty hunter. The rest is television history…

But much as this writer is a long-standing fan of Blake’s 7, it would be a gross disservice to the memory of Thomas to only wax lyrical about –inescapably– his most famous television starring role, without mention of his many other significant leads in numerous other television series of –in particular– the 1970s, that still-unchallenged golden era of character-and-script-based theatrical television drama.

After cameos in some late Sixties series such as Z-Cars and a recurring role in Parkin’s Patch, Thomas began to land leading parts in some highly significant TV plays and serials of the Seventies and Eighties. He won acclaim for his portrayal of a Welsh policeman sent to break a strike of tin miners in Cornwall in the superlative Play for Today, Stocker’s Copper (1972). He appeared in the film of Harold Becker’s The Ragman’s Daughter (1973), as foil to Iain Cuthbertson in Sutherland’s Law (1973), and in the TV adaptation of David Copperfield (1974). One of Thomas’ most memorable roles was as the community-oriented clergyman Mr. Gruffyd in the excellent 1975 adaptation of Welsh mining saga How Green Was My Valley (miles better and more authentic than the much-lauded by highly flawed Hollywood film version of the Forties). Thomas also appeared in Who Pays the Ferryman? (1977).

There then came a kind of hiatus of science fiction parts, all strangely overlapping one another in that, time and again, Thomas was cast as futuristic rebels/radicals/dissident leaders in dystopian series. This tended to belie the impetus behind his later retiring from his biggest role, in the aforementioned Blake’s 7, for fear of being typecast; indeed, one might argue his getting the role of Blake was in itself related to perceived ‘type’. In 1976 he appeared as rebel Shem in the rather garish gender-politics sci-fi series Star Maidens (ITV); then, in 1977, he headed the cast of the remarkably eerie and quite extraordinary children’s serial Children of the Stones (once more opposite Iain Cuthbertson), in which he played a scientist, Adam Brake, whose surname uncannily prefigured that of his most famous role, acquired the following year…

Blake’s 7 was an ambitious melange of Robin Hood- and/or William Tell in space and George Orwell’s 1984 all mingled with polemic on the contemporaneous Troubles and conflicting perceptions of terrorism and perceived fanatical causes, with the only genuine nod to US sci-fi series Star Trek, to which it is so erroneously compared, being the use of teleport (though Blake’s 7 had much more in common with its cousin series Doctor Who: its sets, costumes, writers and producers were all borrowed from Who).

Otherwise, Blake’s 7 was a highly charged studio-video Jacobean chamber piece drama which just happened to be set in the future and have film-location insert action sequences to attempt to compete with the Star Wars momentum of the time; it was gritty, unpredictable, character-driven drama, almost, one might say, costume-drama of the future, in its combination of Shakespearean actors in the leads and the imaginatively cod-medieval costume designs for the main protagonists; Blake, for instance, often wearing leather jerkin and billowing doublet shirt-sleeves. In spite of Paul Darrow’s enigmatic turn as leather-clad, crop-haired, Plantagenet-nosed Avon, who inherits the super-ship Liberator after Blake disappears on an alien planet, the series was never quite as gripping again as it had been when Thomas took centre stage, grounded by Avon’s Ricardian antagonism.

Thomas went on to appear for a time in cameo roles in other notable series of the period: he was acclaimed for his portrayal of a Welsh hill farmer in Morgan’s Boy (1984), also making a cameo appearance the same year in the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes’ episode, The Naval Treaty, as the villain, opposite Jeremy Brett. He also appeared in the supernatural portmanteau series Shades of Darkness (1983), and the TV adaptation of C.P. Snow’s series of polemical novels, Strangers and Brothers (1984).

In 1987 (though actually filmed in 1985), Thomas starred opposite ex-Doctor Who actor Patrick Troughton as a futuristic King Arthur-like figure –and, again, dissident leader– Owen, in the dystopian Wales-set sci-fi drama Knights of God. This role was almost a combo of his previous roles, Blake and Morgan. Somehow the curly-haired Thomas always seemed to fit the shoes of the rugged-but-gentle-hearted, rough-hewn outcast, and his inherent Welshness fitted this well, as it also gifted him a memorable and impressive gravel-voice. In many ways, Thomas was almost made to play Thomas Hardy’s Gabriel Oak on television (indeed, there are some similarities in ruggedness of physiognomy and physique with Alan Bates who played Oak in the 1967 film of Far From the Madding Crowd).

Perhaps Thomas’s least sung but one of his most interesting roles was as Roundhead Major General Horton, a romantic-heroic part, in the second series of English Civil War costume drama By the Sword Divided (1985). As an amateur scholar of this particular historical period, this writer can vouch for the aforementioned series’ unrivalled authenticity of the period it depicts, in his opinion, never bettered before or since (save in the Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo’s consummately authentic Winstanley,1975), not least by the rather perfunctory 1970 film Cromwell; but it is the lesser known second series, in which Thomas’s character figures large, which is of particular note in its detailed depiction of the late Civil War, post-Caroline and Commonwealth periods.

In many ways, Thomas was the kind of actor who could probably only have acquired lead and sometimes romantic roles as he did in the Seventies, a decade peculiarly open-minded in its notions of what constituted lead role material, often going for the gravitas of an actor as opposed to his good looks. For Thomas was a modestly handsome actor, not particularly striking, yet still always memorable, gently masculine in presence and voice. These were key qualities which marked him out for some significant heroic roles in spite of his fairly average looks. Contrary to the popular image of Thomas, of his virile ruggedness and Welshness, he was actually educated privately at Canterbury, and even spent a year at Oxford, before entering RADA. But ultimately he was, as his most popular roles – Gruffyd, Shem, Blake, Horton, Owen– portrayed, a man of and for the common man. Indeed, in his most iconic role, Blake, Thomas’s gravelly intonations immortalised many lines: “Not until power wrests with the honest man”, or “The lightning rain snatched me from the jaw’s of death doesn’t quite ring true this time”. His passing marks the end of an era of halcyon folkloric television heroes.

Alan Morrison © 2016

Obituary

Norman Buller, Poet

15th February 1927 –

7th January 2021

It is with much sadness I come to write this obituary of poet Norman Buller with whom I had the pleasure of being in regular phone and email contact for some years.

First the facts of Norman’s life and poetry career,adaptedand fleshed out from his publisher Waterloo Press’s summary.

Norman William Buller was born and grew up in Birmingham, England. After National Service in Egypt, Palestine and Cyprus, he returned to education at Fircroft College in Birmingham, and went on to read English at St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge. He became one of the Cambridge poets of the early 1950s and his verse appeared in magazines and anthologies alongside that of Thom Gunn and Ted Hughes. From the mid-1950s for about twenty-five years he wrote very little. His occupation was in careers advisory work at the universities of Sheffield, Queen’s Belfast and Birmingam. While at Belfast he took part in Philip Hobsbaum’s creative soirée alongside Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley et al, but throughout that time published just one pamphlet, Thirteen Poems, in 1965.

But Norman flared back into print 40 years later with a pamphlet Travelling Light (Waterloo, 2005). Four full volumes followed: Sleeping with Icons (Waterloo, 2007), Fools and Mirrors (2010), Powder on the Wind (2011), and Pictures of the Fleeting World (2013), all highly praised by critics such as William Oxley, Roland John and Will Daunt in journals such as Acumen, Agenda, Cambridge Left, Envoi, Gravesiana,The London Magazine, Oasis, Outposts, Poetry Salzburg Review.

Between 2008 and 2013 I was in regular phone and email contact with Norman, a fellow Waterloo Press poet,our correspondence often in the capacity of my typesetting and writing the blurbs for his volumes. Helping out as I used to with submissions to the press, I had recommended a manuscript of Norman’s to Waterloo’s chief editor Dr Simon Jenner, which resulted in the slim pamphlet collection Travelling Light (2005). Norman’s prolific body of poetry scrupulously drafted during the course of the previous couple of decades provided enough material (and all accomplished) to fill a good few volumes for the foreseeable future, and since Norman also had a sizeable and very loyal readership, it was feasible for the press to publish his collections at relatively short intervals. Since many of his readers were happy to ‘subscribe’ to his collections by way of pre-orders, each of his collections had effectively sold out before they wereeven printed.

During the time I was in contact with Norman he made significant headway as a contributor of poetry and critical monographs to many high profile literary journals, perhaps most regularly, The London Magazine, during the tail-end of the late Sebastian Barker’s editorship and through into Steven O’Brien’s. As well as many poems, Norman also contributed several critical pieces to said journal, contextual appreciations of landmark poems by esteemed past poets that had left lasting impressions on him, these included ‘W. H. Auden and ‘September 1 1939” and ‘W. B. Yeats and ‘Sailing to Byzantium’’.

It was actually at a London launch of an issue of The London Magazine in 2011 to which both of us had been invited as contributors that Norman and I met in person for the first and only time, but it was an extensive meeting and one which Norman and his wife Ursula had travelled 160 miles by taxi from Worcestershire to get to. The main fragment I remember from our long conversation was Norman mentioning when he’d met Dylan Thomas who had come to do a reading at Cambridge when he was a student there and of how down-to-earth the legendary Welsh poet had come across to him at the time.

Coming from a relatively humble background in Birmingham, it was a considerable achievement that Norman –who started his working life as a toolmaker’s apprentice–made it to St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, a personal accomplishment indicative of the wider transformative postwar social meritocracy of that Pelican-educated Richard Hoggart generation. It was at Cambridge that Norman first made his mark as a budding poet and had an influence on the young Thom Gunn’s poetic development.

Norman’s poetry was a highly refined, exacting and disciplined lyricism, his poems often fairly short to middling in length (he didn’t go in for long poems and it was rare for his poems to go onto a second page).There was a definite orientalism to his style, he often composed haikus and poems of similar forms, and this element was perhaps most exemplified in his 2013 volume Pictures of the Fleeting World.

There were Yeatsian, Gravesian and Audenesque qualities to Norman’s verse, some similarities to Bernard Spencer, and to a contemporary, Donald Ward (d. 2003 one year shy of Norman’s94 years) who had been published by Frome-based Hippopotamus Press which I seem to recall had been Norman’s first port of call for publishing his work, and which would have, had the imprint not been cutting back on its list at the time he submitted to them. Norman’s main influences were W.B. Yeats, D.H. Lawrence, W.H. Auden and Robert Gravesand in their tall shadows he cultivated his own individual voice.

Norman was also passionate about art and many of his poems were ekphrastic tributes to various past artists and artworks, particularly Post-Impressionists, and Expressionists. He once relayed to me a touching story of how he came to specialise in ekphrastic poetry: it had started with an epiphany when extemporising what he imagined was being depicted in a Japanese print on his wall. This Damascene moment led Norman into a whole new approach to his poetry which he put eloquently to me once in an email: ‘I began looking at other paintings and found I could produce successful poems from them… the new poems, when successful, were… re-presentations of my experience of the objects rather than mere descriptions of them. In other words, I had become what Keats called ‘the chamelion poet’, one who became so identified with the object that he, as himself, had, for the purpose of the poem, transposed into it.’

Norman was very careful with his time, choosing to use it mostly in pursuit of his poetic craftsmanship. If not drafting his poetry, he’d busy himself promoting his collections, some of which were audio-accompanied in the form of CD samplers he made in a hired recording studio, whereby readers were treated to his meticulous recitations. He also read at a number of literary festivals including Ledbury.

Norman always came across to me as a kind-hearted, gentlemanly, scrupulously articulate person, extremely warm and polite. I feel honoured to have known such a fine poet of a much earlier generation and with whom I felt so much in common. The British poetry world has, probably without knowing it, lost one of its finest craftsmen, and it can only be hoped that the rest of Norman’s oeuvre will eventually see print posthumously. It seems appropriate to close on one of Norman’s dictums: ‘All each of us can do is try always to produce the very best work of which we are capable by whatever means we can.’ Norman did so demonstrably.

Norman is survived by his wife Ursula, two daughters and a son.

Alan Morrison © 2021

Obituary

Norman Buller, Poet

15th February 1927 –

7th January 2021

It is with much sadness I come to write this obituary of the late poet Norman Buller with whom I had the pleasure of being in regular phone and email contact for some years in the early Noughties and also to meet in person on one occasion.

But first the facts of Norman’s life and poetry career.

Norman William Buller was born and grew up in Birmingham, England. He was educated at Fircroft College in Birmingham and St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge, where he read English. He became one of the Cambridge poets of the early 1950s and his verse appeared in magazines and anthologies alongside that of Thom Gunn and Ted Hughes. From the mid-1950s for about twenty-five years Buller wrote very little. His occupation was in careers advisory work at the universities of Sheffield, Queen’s Belfast and Birmingam. While at Belfast he took part in Philip Hobsbaum’s creative soirée alongside Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley et al, but throughout that time published just one pamphlet, Thirteen Poems, in 1965.

Buller flared back into print 40 years later with a pamphlet Travelling Light (Waterloo, 2005). Four full volumes followed: Sleeping with Icons (Waterloo, 2007), Fools and Mirrors (2010), Powder on the Wind (2011), and Pictures of the Fleeting World (2013), all highly praised by critics such as William Oxley, Roland John and Will Daunt in journals such as Envoi, Poetry Salzburg Review,The London Magazine, Cambridge Left, Acumen, Agenda.

Between 2008 and 2013 I was in regular phone and email contact with Norman, a fellow Waterloo Press poet,our correspondence often in the capacity of my helping out with book designs, typesetting and blurb-writing for the imprint, including for all his volumes. I had recommended a submitted manuscript of Norman’s to Waterloo’s chief editor Dr Simon Jenner,which resulted in the slim pamphlet collection Travelling Light (2005). Norman’s prolific body of poetry scrupulously drafted during the course of the previous couple of decades provided enough material (and all accomplished) to fill a good few volumes for the foreseeable future, and since Norman also had a sizeable and very loyal readership, it was feasible for the press to publish his collections at relativelty short intervals. Since many of his readers were happy to ‘subscribe’ to his collections by way of pre-orders, each of his collections had effectively sold out before they wereeven printed.

During the time I was in contact with Norman he made significant headway as a contributor of poetry and critical monographs to many high profile literary journals, perhaps most regularly, The London Magazine, during the tail-end of the late Sebastian Barker’s editorship and through into Steven O’Brien’s. It was actually at a London launch of an issue of The London Magazine in 2011 to which both of us had been invited as contributors that Norman and I met in person for the first and only time, but it was an extensive meeting and one which Norman and his Bavarian-born wife Ursula (whom he called Uschi) had travelled 160 miles by taxi from Worcestershire to get to. The main fragment I remember from our long conversation was Norman mentioning when he’d met Dylan Thomas who had come to do a reading at Cambridge when Norman was a student there – I seem to recall Norman describing Thomas as “rather dishevelled”.Norman certainly wasn’t dishevelled, in suit jacket and bow tie, atop which snowy shoulder-length hair and a short white beard gave an almost wizardly impression, or that of an eccentric antiques dealer.

Norman always came across to me as a kind-hearted, gentlemanly, scrupulously articulate person, extremely warm and polite. He was immensely proud of having made it to Cambridge University from a relatively humble upperworking-class background in Birmingham, and perhaps this was also partly why he was so fascinated by the life, work and character of DH Lawrence. His other main influence had been WB Yeats. Norman himself had been an influence on the young Thom Gunn.

Norman was very careful with his time, choosing to use it mostly in pursuit of his poetic craftsmanship. If not drafting his poetry, he’d busy himself promoting his collections, some of which were audio-accompanied in the form of CD samplers he made in a hired recording studio, whereby readers were treated to his meticulous recitations. He also read at a number of literary festivals including Ledbury.

He often advised me to spend less time reviewing other poets, and to spend almost all my time working on my own poetry – I think he meant that there were ‘critics’ to do the former while poets should purely focus on their own output, but that was perhaps a generational perception since increasingly most poetry critics are themselves poets. I’ve always spent most of my time working on my own poetry, but sometimes it’s felt appropriate to me to critically analyse the poetry of some of my contemporaries – this can be poetically nourishing in a different sense and help to enrichen one’s own writing in all sorts of different ways. Sometimes it’s important to take a step back from one’s own work and take stock of what others are doing. But Norman set himself one particular rule for when he did occasionally write a critical piece or monograph on another poet: they must be deceased –and, as importantly, have a strong posthumous track record. For whatever reasons, he did not believe in reviewing living poets (though he once made an exception for Derwent May). His approach was usually to analyse and contextualise a famous poem by a famous past poet, and these essays included the astute and erudite ‘W. H. Auden and ‘September 1 1939” and ‘W. B. Yeats and ‘Sailing to Byzantium’’, both published in The London Magazine.

On Norman’s poetry: his was a highly refined, exacting and disciplined figurative lyricism, his poems often fairly short to middling in length (he often commented to me that he didn’t go in for long poems and it was rare for his poems to go over onto a second page).There was a definite orientalism to his style, he often composed haikus and poems of similar forms, and this was perhaps most refracted in his 2013 volume Pictures of the Fleeting World. There were definite Yeatsian and Audenesque qualities to Norman’s poetry, some similarities to Bernard Spencer, and to a contemporary, Donald Ward (d. 2003 one year shy of Norman’s94 years) who had been published by Frome-based Hippopotamus Press which I seem to recall had been Norman’s first port of call for publishing his work, and which would have, had the imprint not been cutting back on its list at the time he submitted to them. Needless to say these influences in no way detracted from the distinctiveness of his individual voice.

Norman was also passionate about art and many of his poems were ekphrastic tributes to various past artists and artworks, particularly Post-Impressionists, and Expressionists. He once relayed to me a touching story of how he came to write so much ekphrastic poetry: it had started with an epiphany when extemporising what he imagined was being depicted in a Japanese print on his wall. This Damascene moment led Norman into a whole new approach to his poetry which he put eloquently to me once in an email: ‘I began looking at other paintings and found I could produce successful poems from them…the new poems, when successful, were… re-presentations of my experience of the objects rather than mere descriptions of them. In other words, I had become what Keats called ‘the chamelion poet’, one who became so identified with the object that he, as himself, had, for the purpose of the poem, transposed into it.’

I feelhonoured to have known a fine poet of a much earlier generation than my own and yet one with whom I felt so much in common – some qualities, I suppose, are ageless. Norman and I often mutually lamented the tragic erosion of the postwar consensus and social democracy in Britain since Thatcherism. Norman was very much a product of postwar social meritocracy, of the Pelican-educated Richard Hoggart generation, while I was, am, I suppose, something of a throwback to it, a hauntological nostalgist. The term Norman frequently used to describe the moral regression he generally perceived in post-Thatcherite society was ‘decadent’, which he’d pronounce as if negotiating a bad taste in his mouth.

The British poetry world has, probably without knowing it, lost one of its finest craftsmen, and it can only be hoped that the rest of Norman’s oeuvre will eventually see print posthumously. It seems appropriate to close with Norman’s words on how he saw the poet’s mission: ‘All each of us can do is try always to produce the very best work of which we are capable by whatever means we can.’ Norman Buller was a poet who did so demonstrably.

Norman is survived by his wife Ursula and daughter Anthea.

Alan Morrison © 2021

Below I reproduce the critical blurbs I wrote for Norman’s final three Waterloo volumes, since these give detailed summations of each respective collection inclusive of excerpts from his poems.

Norman Buller’s second full collection confronts the universal prism that Fools and Mirrors us. Behind the prosodic elegance beats an earthy vitalism that tussles with a disembodied, spiritual distrust of the physical – a fascinating dynamic. ‘Portraits by Francis Bacon’ captures the tortured carnality of that artist’s work, its misanthropic grotesquery provoking the poet’s Gulliverish revulsion at the animal in us. But Buller’s pessimism is more sceptical than devout, and when saying ‘we dream a sense of purpose/ …the rest is meat’, a sense of salvation triumphs in the beauty of such phrasing.

In stark contrast is an appetite for Lawrentian symbolism: ‘roadsides yellowed/ by phalluses of broom’. A poet deeply sceptical of the turn society has taken over the last three decades, Buller’s work is alert to an encroaching decadence that most pretend isn’t there. His is a humanistic politics that laments the post-war consensus, while quietly accusing capitalism of its gradual dismantling; from Aldermaston to the eerie blue skies of Manhattan 9/11.

In a more theological vein, Buller probes the spiritual life of Martin Luther, and, antithetically, Cardinal Newman, and Pope Innocent the Tenth via Velasquez. This detour through Catholicism echoes the Thomism of David Jones’s oeuvre: art as sacrament. There are portraits of Kandinsky, Klee, Chagall, and Walter Sickert via a model’s cockneyish idiom. Aphorisms flourish: ‘A church bell summons the faithful./ Something will endure’, or the sublime ‘…I wring your shadow in my hands’.

Alun Lewis and Dylan Thomas haunt ‘and night again prepares to bear/ the village away in sleep’, while ‘Dear Gerard’ ghosts Manley Hopkins uncannily. Such echoing of past voices, no mere pastiche, is almost mediumistic. The book’s core theme is mortality and the artist’s impulse to transcend it: ‘The poet aspires to the condition of art,/ a thing made which outlasts its maker’. Buller’s is a voice of endurance through self-transcendence whose historical verisimilitude makes for a more vital addressing of the present.

*

Powder on the Wind — adumbrated by the critically praised Sleeping with Icons (2007) and Fools and Mirrors (2010) — is a thornily haunting, icily penetrating collection that casts its own distinct shadow. Buller’s authorial humility is as ever marked by a fascination with other creators’ lives — here, Gwen John, Elizabeth Bishop, Walter Sickert among them — paid tribute in figurative miniatures. These poetic portraits take shape either in appreciations of — often unmanageable — talents, orempathetic projections, as if tapping the subjects’ after-thoughts on the spiritualisttable of the page. Buller is also visited by three Russian poet-spectres: BorisPasternak — ‘Take my life from the shelf and blow its dust away;…/ I’ll make theblank page flower if I must…’; Marina Tsvetaeva, spitting metaphors at pastslanders — ‘…that I’m a harlot sprawling/ in a drunken Russia’s arms’; and OsipMandelshtam, who feels as if ‘…rolled on [the] tongue’ of the Red Tsar ‘like a berry’.Buller’s absorption in the blasted tundra of Russian literature sets a bitingly wintrytone. Mortality’s inescapability is sprinkled like permafrost throughout, coldlyindefatigable as the mind’s tireless instinct to negotiate terms. Buller’s antidoteis the holiness of the moment’s insight, defined entirely by time — the explicitterritory of poetry, and love: ‘Here soul and spirit play/ the roles our bodies fix’.This Lawrentian naturalism runs through Buller’s thought and technique, but is lit by embers of metaphysical tension. A half-reconciled agnosticism cannot ignorethe wires of religious legerdemain, nor shrink from imponderables, such as thepossibility of an afterlife utterly unrelated to our earthly one: ‘Suppose our soulsincline/ to worlds beyond this place;/ there love will play by different/ rules fromours’. Thumping down to earth are more mud-splattered portraits, of RobertGraves’ ‘neurasthenic terror’, and Isaac Rosenberg, ambered in sublime aphorism‘wearing/ poverty as his albatross’. Powder on the Wind firmly establishes Bulleras a forceful lyric voice; one in the timbre of poets such as Bernard Spencer (whose peregrinatory qualities Buller also echoes) and the late-flowering Donald Ward.

*

Norman Buller’s Pictures of the Fleeting World signals new departures into more crystallised lyricism, with oriental tints. The double section ‘Studies and Variations in the Japanese’ pays homage to the 18th and 19th century Japanese exponents of Ukiyo-e (wood block prints) – Utagawa Hiroshige, Utagawa Kunisada et al – in a series of exquisite miniatures. Tributes to past artists explore the psychical landscapes of Rembrandt, Turner and Matisse throughappreciation of some of their most expressive paintings: ‘she is formed deepfrom/ his cave of desiring,/ lingering odalisque/ ghost in the mind’ (‘Matisseand the Dancer’). This sensibility ripens in the sublime ‘Edgar Degas’, depicting the ‘painter as eunuch’, while his studies of bathing women framefigurative peepholes which compromise the viewer as voyeur. There is a Munchian quality to elliptical portraits such as ‘Daisy in the Garden’, and the Picasso-themed ‘Weeping Woman’: ‘a handkerchief grinds/ in her frenzied teeth.// Her face is collapsing’. Aphorisms on ephemerality are couched in Audenesque meditations: ‘memories/ outlive graves/ yet die with their possessor’ (‘A Garden Remembered’). Buller’s metier dovetails between themes of mortality and vitality; even virility, as in the Lawrentian ‘Nevermore’: ‘Observe the motif, labia wide,/ and see the risen phallus slide/ between those ever-open jaws’. In ‘The Cave’, a rare self-portrait from a poet who normally shies from introspection, Buller triumphs with a trope which might be an epitaph for the poetic species as a whole: ‘I write for myself and the/ hypothetical other’. Pictures of the Fleeting World is as its title suggests: a gallery of richly captured moments.

Alan Morrison © 2010, 2011, 2013.

Obituary: Brenda Williams (10 Dec 1948-19 July 2015)

Brenda Williams, poet and protestor, was born on 10th December 1948 in Leeds, the eldest child of four. Her two younger brothers and sister have survived her.

The circumstances in which Williams grew up were dire: she lived with her parents and three siblings in a damp basement in a relative’s house; later the family progressed onto a council house.

Williams’ father was an alcoholic and could be abusive, sometimes beating the children. Brenda’s mother, an Irish Roman Catholic immigrant, was often terrified by her husband’s behaviour, and Williams remembered from an early age being taken out into street by her in order to avoid her father’s raving. Such traumatic experiences marked her for life.

Williams could have gone to grammar school but her parent’s couldn’t afford the school uniform. Her mother was an auxiliary nurse; her father always worked but spent much of his money in the pub –this taught his daughter from an early age that to be in work, to be employed, did not necessarily bring with it greater virtues.

Passing four O Levels and gaining an A Level in English Literature, Williams aspired to being a teacher, but ended up working as a library assistant. It was by dint of this occupation that she met young teacher and aspiring poet, Barry Tebb, via a mutual friend he taught with. Tebb’s curiosity was stirred by Brenda’s habit of reading Proust while working at the library; and after asking her out for a coffee following another meeting at a house warming party, Tebb soon realised that he and Williams were soul mates.

The couple married in 1967. Tebb’s poetic ambitions led them to take up a secluded, domestic life in an isolated cottage in Huddersfield. Williams, however, never settled to such a Wordsworthian retreat, so the couple moved to a more urban environment. Around this time, Williams gave birth to their son, Isaiah (for Williams, the first of two sons, her second, Ezra, from a subsequent relationship).

Williams and Tebb divorced in 1975 after eight years married. However, the two remained extremely close, Barry moving to a council house in the street next to Williams’ newly bought house, in Leeds.

Williams started writing poetry in late Seventies, and began having poems published in magazines. Around 1990, Tebb started up his own imprint, Sixties Press, under which he published his own and Williams’ work, alongside other distinctive but ‘unfashionable’ poets. Tebb managed to gain many sponsors for his small press imprint, including Rowan Williams (some time prior to his Archbishopric of Canterbury), with whom he had struck up poetic correspondence.

Their son, Isaiah, passed exams to get into Leeds grammar school (which poet Tony Harrison had attended). Around this time, Williams applied to Leeds University as a mature student, but was inexplicably rejected. This unfortunate stumbling block, however, saw Williams the poet assert what would become the other cardinal ingredient to her character: the protestor. Williams did sit-ins at Leeds University in protest against her unexplained exclusion, while Tebb, ever loyally, trooped the corridors of the establishment until he found out the reason for it. It turned out that her entry had been blocked by a ‘professorial veto’ issued by theology lecturer David Jenkins (later to become the Bishop of Durham) who disapproved of her having an illegitimate child (Ezra). Unfortunately, however, Williams’ protest was not efficacious on this occasion.

Ever close to one another, Williams and Tebb both moved to Oxford, still living separately, but close (echoes of Hardy’s Jude Fawley and Sue Bridehead). Ironically, Williams had finally and belatedly been offered that place at Leeds University, on the eve of their departure for Oxford. It came too late. They didn’t tell Leeds grammar school that they were moving with Isaiah from the area, which meant that their son was not transferred to Maudlin Grammar School, Oxford, as would have normally been the procedure. This second educational vicissitude spurred Williams to set up public protest in their new home town. This time she at least gained national publicity through a full page feature in the Times Educational Supplement. Absurdly, she had been arrested for ‘obstruction’ by an Oxford policeman, in spite of her pitching daily on a nine foot wide pavement. Subsequently the case was dismissed.

Williams now aspired to live in London, and felt St. John’s Wood had a particularly poetic sound to it, so moved there into a sub-let flat facilitated by Tebb, who, again, moved with her, settling nearby in Chiswick. Williams would remain in this flat for the rest of her life. Tebb would meet his second wife, another poet and fiction writer, Daisy Abey, while attending the Buddhist chapel opposite his new flat. Tebb, Williams and Abey all got on well together and remained a fond triumvirate.

Williams became a prolific protestor following her move to London. Perhaps her most well-known protest was in 2007, campaigning for better treatment from the mental health system in Camden and Islington. She pitched daily outside the Royal Free Hospital, since this was a central site. Camden Council, under all three main parties, continually tried to have Williams evicted from her protest pitch and arrested, her placards being constantly seized from her. These events were covered in lots of local newspapers at the time. Protesting alongside Williams was her close friend, Gertrude Falk, a leading physiologist and Hampstead Labour Party campaigner whose obituary in The Guardian (Weds 2 April 2008) mentioned her stint with Tebb and Williams outside the Royal Free. Williams, how own mother had died when she was just fifteen, had come to regard Gertrude Falk as a surrogate mother.

Williams suffered from severe depression throughout most of her life, spending lots of time at West Hampstead Day Hospital where art therapy helped her. She responded well to the compassionate approach of a psychiatrist, Dr. Peter Raven, who was also Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry at the Royal Free. Williams’ other source of human comfort was her indefatigable friend and ex-husband, Tebb, who continued to encourage her poetic efforts, from which she drew much strength.

Williams’ life was rendered more complicated and stressful due to the course her eldest son Isaiah’s took: after an auspicious educational start to his life (Eton, then Baliol Oxford), he descended into chronic paranoid schizophrenia, and remains hospitalised to this day.

Williams became an elected patient governor at Camden and Islington, and was in the middle of her third term when she died. She went to all the meetings, but her depression had been getting worse. Her mental health issues were exacerbated by trouble in the block of flats where she lived: a multi-propertied landlord bought up most of the block (on monies borrowed from the pre-Crash RBS, in 2007) where he ran a rental racket, herding Turkish-German tenants into the flats, charging them exorbitant rents underwritten Housing Benefit, and then, due to short-term tenancies which left the tenants with virtually no rights, evicting them. This 1920s block was constantly racked by intrusive noise as the property developer had his flats renovated. True to form, Williams set to protesting outside the block, which, by dint of being her own place of residence, meant her protest was legal.

Tebb believes that this, Williams’ last ditch protest, in part, contributed to the acceleration of her frail health, and subsequent untimely death; not least since Williams spent on average between eight and ten hours a day pitched outside the block of flats (141 videos on Youtube document it). Williams was diagnosed with lung cancer at the Royal Free in late December 2013, after a persistent cough did clear up with antibiotics. The supposition was that Williams, who had never smoked, had inherited a genetic predisposition to this particular cancer. She had already been perilously ill with a perforated bowel.

Williams’ treatment was transferred to the Marsden (via Tebb’s petitioning due to not being satisfied with her treatment at the Royal Free), but by this time the lung cancer was at ‘spread stage 3’, cellular and incurable. Williams was given a prognosis of 18 months. Then, in 2014, her cancer was unexpectedly deemed ‘77% cured’. However, sadly, by January of this year, the cancer again intensified, in spite of continual chemotherapy, and her doctor gave her 3 to 4 months to live, though she managed to live another six months.

A compulsive and prolific poet, Williams was still writing only a few weeks before her death, on 19th July 2015. Her final poem was the pointedly titled ‘Words Towards an Obituary’. In the last few years of her life, Williams became ‘obsessed’ by the sonnet form, producing hundreds of poems in this fourteen line structure, her ambition being to outnumber Shakespeare’s. In her will, Gertrude Falk had left Williams £6,000, which was used to pay the printer to publish a large number of copies of her Collected Poems, under Tebb’s Sixties Press imprint. Shortly before her death, Williams made Tebb, her lifelong soul mate, friend, champion, carer and custodian of her many cats, her official ‘next of kin’ and, implicitly, publisher and executor of her literary estate. (Posterity will tell if the lifelong mutual devotion and trysts of Tebb and Williams might one day join the canon of the likes of Graves and Riding, Barker and Smart, Hughes and Plath, Redgrove and Shuttle et al).

Finally, some words from this writer: it was my pleasure to have met Brenda once and fairly briefly, but memorably, when she attended the launch reading of Emergency Verse – Poetry in Defence of the Welfare State at the Poetry Library, Southbank Centre in January 2011. I recall in particular how friendly, warm and effusive she was towards me, seemingly delighted at the anthology and its attempt to make a poetic stand against the then-new Tory-led Coalition Government. Brenda simply said that she had to “hug” me for my effort, and promptly did so.

This was a real surprise for me since I’d been led to expect a dourer person from the description given of her by someone to whom she had presumably not felt particularly enamoured. Like Barry (Tebb), Brenda did not suffer fools gladly, but was demonstrably someone who would warm instantly to anyone who was of a similar wavelength and values (poetical and political), and I felt privileged that she warmed to me on our first and only meeting.

When, some months on from that launch reading someone I had previously counted as a friend and poetic champion, the veteran poet and reviewer, John Horder, triangulated a highly personalised and irrational critical assault on Emergency Verse (via a three-pronged duplication/circulation in the Camden Review, West End Extra and Islington Tribune), in spite of his having attended –in Brenda’s company– and read at the launch (though not as a contributor to the book, for my having not been able to get hold of him for permissions while selecting for it –hence, presumably, his sudden animus against me!), I was deeply touched when Barry told me how “incandescent” Brenda was on my behalf. She apparently promptly annulled her long-standing friendship with John as a result.

Brenda realised the importance of that anthology, at such an ominous and hopeless time politically, but also, as Barry related, felt genuinely aggrieved and angry on my behalf after the considerable effort and labour I had gone to in producing the 111-poet-strong tome, replete with epic polemical Foreword and Afterword. I remain forever grateful to Brenda for her empathy, respect and loyalty –loyalty, only after having met me once!

Alan Morrison © 2015

Brenda Williams (10 Dec 1948-19 July 2015) is survived by her sons Isaiah and Ezra, by her two younger brothers and sister, and a grandson.

Click here to read a selection of Brenda Williams’ last composed poems which it is The Recusant’s privilege to publish here for the first time.

Click here for two tribute poems to Williams by her ex-husband and lifelong friend and carer, Barry Tebb.

Words towards an Obituary for Poetry

This is a road I never thought to know

Where memory is mimicking the end,

The future descends on the faculty

Of my soul, my mind struggling for a foothold in

Existence, always the poem, always

The unheard, there is nothing in my hands,

I leave with nothing this world understands.

Unimaginable those early days

The spirit conjuring its poetry,

Forgiveness he cannot borrow or lend

Words unfinished as the first light of day,

Lost as they are, forever on the way

The flickering candle he cannot trim

The undesciphered script of tomorrow.

Brenda Williams

7th July 2015

Your Dying

How can I endure winter without you, sad divine daughter of September?

Your calls outlast autumn’s miasma, the hesitant tone of your final poem

‘Towards an Obituary’, self-questioning, plaintive Keatsian ardour,

Harbour of all your griefs, your mother’s slow death from cancer,

Denied the bus fare for her last hospitalisation.

When they said you were terminal, “Three or four months and a bit”

You tried hard to finish ‘The Poet’, ‘Brian’s Not There’, ‘Forever Young’.

It was hopeless, so you fled to the South Bank to watch the films

You’d missed, a season of Siodmak, Welles in ‘Chimes at Midnight’.

You managed a whole Saturday, Hardy’s ‘Under the Greenwood Tree’

In three two hour episodes but the next day

You phoned at seven, “Please get me into hospital”.

It was the last time, after twelve days they moved you

To the hospice, I sat in the transfer ambulance,

You were strapped down and I strapped up, too far

To grasp your desperate hand. For once your terror was plain,

You’d never come home to your eight cats again.

I was the only visitor to the hospice, save Daisy

To assure your cradle Catholic soul of a Christian burial.

In those last twelve days you awaited death while I,

Hopeless and stunned, listened for your last breath.

Brenda Williams

10th December 1948 – 19th July 2015

Only music can stem the blood wrench of my heart

Your death began but nine weeks on

Every day your absence wakes me at four a.m.

I can never tell you how much I miss you

Words flowed between us like a river.

Barry Tebb

The Closed Door

for Eli Williams, aged four days

The Moving Finger writes; and,

having writ,

Moves on; nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a

Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word

of it.

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

So soon, too soon, my grandson was torn from

Me, my lifeless arms left empty of him,

Never having known our newborn embrace,

Nor ever having seen his first known face.

I exist now with the memory of

You already, our brief life forbidden,

A candle, burnt out, before it even

Had a chance to soar, to magnify my

Dreams in the silence of time and to make

Them last for evermore. Before you were

Ever born, you kept me alive for nine

Months more, anchored at the core of being

To the closed door to come. How to endure

When time is no more than a starless shore.

Brenda Williams

13th August 2014

2

The world is larger now that you are here,

A new frontier palpable and sheer,

The days sear far into the stratosphere.

Your memory, perpetually near,

Is a bulwark for the hours as they veer,

The unsalvaged years from Truth and Beauty

Roll back low as though their own tsunami

And wake, and break against infinity,

I hear in the echoing terminus

The last mayday and muted sound of us.

In this bleak world between heaven and hell,

Time was left to spiral in parallel,

Yours was the face I never thought to see,

Unimaginable the time to be.

Brenda Williams

22nd August 2014

For a precious grandson

How I have missed you,

Never having known you

Down the long months.

I am your grandmother,

Brenda, and you will

Become the Keeper

Of my poetry in the years

To come. Welcome dear one

19th November 2014

Brenda Williams

Poet and Nurturer

A Tribute to Sebastian Barker

(16 April 1945 – 31 January 2014)

It is with much sadness that I recently learnt of the death of poet and editor, Sebastian Barker (FRSL), who passed away after suffering a cardiac arrest at the age of 68, on 14 February 2014. Sebastian had been stricken with lung cancer for some time prior to this, but I had only heard about his condition indirectly, and fairly recently.

The broadsheet obituaries will furnish readers with the full facts of his life and poetry career, but to recapitulate: Sebastian Barker was the son of the prolific British neo-Romantic poet George Barker (1913-1991) and the Canadian poet and novelist Elizabeth Smart (1913-1986), thus brought up in a rather ‘bohemian’ environment. He was educated at the King’s School, Canterbury, and Corpus Christi, Oxford. He was appointed to many auspicious posts throughout his career: Chairman of the Poetry Society (1988-1992); elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1997; and, of course, appointed editor of the London Magazine in 2002. His many poetry collections included: On the Rocks (Martin, Brian & O’Keeffe 1977), A Nuclear Epiphany (Friday Night Fish Publications, 1984), Guarding the Border: Selected Poems (Enitharmon Press in 1992), The Dream of Intelligence (Littlewood Arc, 1992), The Hand in the Well (Enitharmon, 1996).

At the age of 52, Sebastian converted to Roman Catholicism, and his growing fascination with the traditions, thought and symbolisms of the faith informed his later poetic works: Damnatio Memoriae: Erased from Memory (Enitharmon, 2004), The Erotics of God (Smokestack Books, 2005) and A Monastery of Light (The Bow-Wow Shop, 2012). But this was more a mystical than ‘religious’ poetics, very much rooted in Thomism (Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), concepts such as Quiddity (essence), and the signs and symbols of human art as forms of transformative sacrament analogous to divine creation as signified in Catholic ritual (e.g. transubstantiation in the Eucharist), notions which had also heavily influenced Catholic poet David Jones (1895-1974), who wrote a monograph on the subject, ‘Art and Sacrament’ (Epoch and Artist). An article on Thomist influences in the art and poetry of David Jones and Jacques Maritain, ‘Art, Scholasticism, and Sacrament’ by Kate Edwards, appeared in the very last issue of the London Magazine under Sebastian’s editorship, and inspired me at the time to write a poem on the theme, ‘The Plaster Tramp’, which I dedicated to Sebastian, and which appeared in my 2008 volume A Tapestry of Absent Sitters).

My own association with Sebastian came, as it were, in the autumn of his long career, and towards the end of his highly imaginative and influential editorship of the London Magazine. Sebastian was the first editor of an established journal to give my own poetry that much-needed ‘break’ into wider recognition. I was extremely fortunate to have sent a copy of my debut volume, The Mansion Gardens (Paula Brown, 2006), to the London Magazine during Barker’s editorship: not expecting it to be noticed, I was very surprised to find a fairly extensive and mostly positive review of the book in the following issue, by respected poet and critic William Oxley. For a first full volume by a relatively unknown poet published by a relatively unknown imprint to get any exposure in a high profile journal seemed refreshingly against the grain of the predominant journal protocols of hoops and nepotisms, and, I think, was indicative of a very open-minded editorship.

Looking back, I can see that was perhaps the peripeteia in my own nascent poetry ‘career’. Not long after this, I was over the moon to have two poems accepted by Sebastian for another issue of LM, to be followed not long after by another acceptance. By the time of Sebastian’s resignation from LM, I’d come to feel I was becoming a regular contributor to the journal, but there would ensue, perhaps inescapably, a pause of a couple of years before my poems and critical writing would reappear there, under Steven O’Brien’s editorship. During the intervening time, there was a disorienting run of issues where it seemed LM had lost its identity and merged indistinguishably into the postmodernist mainstream, from which it had formerly stood out so distinctly and self-determinedly during Sebastian’s editorship. But the fact is, in terms of my own ‘introduction’ into the higher profile literary journal sphere –along with those of a number of other poets and writers I know– I have Sebastian Barker to thank. When I reviewed the last edition of LM under his editorship, in 2007, I wrote:

No journal genuinely nurtured its contributors as compassionately as the London Magazine under Sebastian Barker’s editorship, and as a recent contributor, I speak from personal experience.

As editor of LM (2002-07), Sebastian was, to my mind, perhaps the foremost progressive, generously spirited and genuinely open-minded of the established journal editors, and in those senses continued in and amplified the historical template of literary liberalism and catholicity exemplified by the LM’s briefest but most iconic editor, John Scott (1820-21), famous for his championing of the otherwise contemporaneously disparaged Romantics (Clare, Shelley, Keats); and for being fatally wounded in an ‘editors’ duel’ with J.H. Christie, close associate of the likes of the rancorous Tory literary critic John Coker, and Dr. John Gibson Lockhart of the Tory Blackwood’s magazine, whose snobbish drubbing of the poetry of Keats and Leigh Hunt as belonging to the ‘Cockney school of poets’ sparked a combustive series of literary missives which eventually drove Scott to take up pistols with Christie. It is a strange irony, given its ‘historied’ progressiveness (originally founded –in 1732– to provide supplemental political opposition to the Tory Gentleman’s Magazine) that, in recent years, the London Magazine –though still among the richest and most eclectic journals around– has come under noticeable Tory patronage; however –and to the journal’s continued credit– this hasn’t seemed to have yet detracted from its sense of aesthetic comity (while, from my own point of view as an occasional contributor, I’m keen to continue submitting material, if nothing else, to help towards keeping up the journal’s historical liberalism; this also gives an unusual opportunity to preach to the unconverted, as it were, which in a way adds to LM’s distinctive polemical eclecticism, and thereby encourages debate).

I was in occasional email correspondence with Sebastian around the time I was setting up The Recusant, and asked if he’d like to submit a poem. He sent me what I seem to recall was actually the first ever poem contribution published on The Recusant, ‘The Quercy Cross’, a beguiling pseudo-religious lyric, which I include at the bottom of this obituary. Sebastian would also later contribute some of his more polemically robust/ satirical verses to the two anti-cuts Caparison anthologies, Emergency Verse (2011) and The Robin Hood Book (2012).

As previously cited, Sebastian’s editorship of LM came to an abrupt end in 2007, when he resigned following the axing of funds to the journal by the Arts Council. I contacted him at that time to express my genuine sadness at his departure from LM, and wrote a polemical comment piece on TR in relation to the subject. I had also offered him an opportunity, if he felt so inclined, to write something on his recent experiences at the LM, for TR, but he was determined to put that whole episode behind him as quickly as he could, and didn’t feel then it was the appropriate time to discuss his perspectives in public (I think he did a couple of years on, in Acumen). This was a very difficult time for him, understandably, but he remained defiant, and optimistic for the future, even if, at this juncture, it was a mistier prospect than it had been for him previously. We tentatively discussed the possibility of working together on a Caparison ebook publication of his then current poetry manuscript, but I’d advised him it was probably better for his interests to hold out until another publisher offered him a print publication (which, I seem to recall, eventually came from Enitharmon).

Sebastian will be sorely missed by many across the broad spectrum of our multifaceted poetry culture, not only as a poet, but also as an editor. Though I never got round to meeting Sebastian face to face –something I now greatly regret– his correspondences, whether by email, or in his beautifully shaped snippets of handwritten, personalised comments at the bottom of the LM’s standardised typed acceptance letters, gave off a genuine glow of openness and hospitality, which one can sometimes detect not simply through content but also care of presentation. And in an era of multi-varied means of communication but exponentially rising solipsism –especially through the unspoken non-protocol of the email ‘licence’ not to reply to or even acknowledge receipt of a message sent, or a seeming misapprehension of some emailers to presume the sender is telepathically wired up to know they’ve received and read their messages!– especially among numerous contemporary poetry journal editors, Sebastian’s sense of basic courtesy and warmness of communication marked him out as perhaps one of the last truly empathic editors –a true adherent to apparently prelapsarian notions of polite appreciation.

And, most crucially, in spite of his prolific and significantly successful literary career, Sebastian had that very rare quality, but one which is, to my mind, essential to the spiritual authenticity of any poet: humility. And humility often seems in short supply in our contemporary poetry culture. It’s hoped, then, that in remembering Sebastian Barker, we might all reflect not only on the poetic but also personable reasons why he is, and will remain to be, so fondly remembered.

The Quercy Cross

There in the shade of the Quercy causse, the cross

Stands, as the bells of St Jean de Laur float over

The green auditorium of thin oak trees.

Patterns of sunlight rearrange their colour

As the wind strokes the oaks and settles down

To the fructification of the forest.

The sun pierces the leaves and stings the ground

With baking pools of stone in this neverest

Of ecclesiastical ascension

Towards the stone cross smacked with gold fungus,

An aureole of butterflies, the neon

Blue of the jet-threaded sky, the cicadas

Penetrating literature, with sharp teeth

Biting out the substance of my living breath.

[First poem published on The Recusant, in 2007]

Sebastian Barker (16 April 1945 – 31 January 2014)

A.M.

3 March 2014

Obituary

R.I.P. Niall McDevitt, poet

22 February 1967 – 29 September 2022

A Blakean Radical

Almost incomprehensibly, radical poet, psychogeographer, poetry historian, activist, visionary and devout Blakean, Niall McDevitt, has passed away at just 55 years of age.

I had the privilege to have met Niall on several occasions over the years, I always invited him to read at any book launches or readings I did in London, a city whose rich literary and artistic history he came to be an expert on and something of a psychical curator through his legendary literary walks. Niall was also an indefatigable campaigner for the preservation of literary sites, including the Rimbaud/Verlaine House at 8 Royal College Street, and the Bunhill Fields graves of Blake and Daniel Defoe.

A self-described flaneur, anarchist, and republican, Niall was unafraid of ruffling feathered nests and throwing down gauntlets before establishments of all kinds. His poetry was richly figurative, deeply polemical; it had Symbolist aspects, and often incorporated pidgin, portmanteaus (‘luxembourgeois’, one of my favourites) and linguistic experimentation reminiscent of such diverse poets as Arthur Rimbaud, DH Lawrence, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, ee cummings, and Allen Ginsberg.

Niall managed in his poetry to merge the historical and contemporary in an almost mystical, shamanic alchemy. This mystical aspect was Niall’s own particular Blakean spark, his having been a lifelong admirer, champion and, one might almost say, poet-apostle of Blake, grasping the immanence and sempiternal qualities of his timeless poetry.

There was something mediumistic about how Niall spoke and wrote about Blake, almost as if he actually, somehow, knew him personally, or at least on a spiritual plane. When I mentioned to him in an email of my move from Brighton to Bognor Regis in 2016, he wrote ‘you’ll be nearer to Blake now’, referring to Blake’s Cottage in nearby Felpham. That was the setting of my penultimate encounter with Niall for his talk and reading during the 2018 Blakefest.

Where I felt a commonality was in our serendipitous dovetailing on themes such as the impecuniousness of poetic occupation and unemployment—his poems ‘Ode to the Dole’ and ‘George Orwell Is Following Me’ (which he performed to the accompaniment of his drum) were staples of his repertoire. Our approaches were very different, but our sentiments chimed. There were sometimes vocabular crossovers in our verses—terms like ‘thaumaturge’, ‘colportage’, ‘grimoire’, ‘tetragrammaton’, ‘euergetism’—almost like poetic telepathies.

Niall’s self-described ‘anti-Tory poetry collection’ and testament to the early austerity years, Porterloo (International Times, 2012), was a satirical masterwork, which I reviewed in detail in 2014 in a three-part monograph on The Recusant titled ‘Illusion & Austerity’. I made sure to include Niall in all three Caparison anti-austerity anthologies: Emergency Verse (2011), The Robin Hood Book (2012) and The Brown Envelope Book (2021). I recall, too, after wrapping up the launch of Emergency Verse at the National Poetry Library in early 2011, Niall spontaneously presenting me with a Blake print in recognition for having put the anthology together.

The last time I saw Niall was at Bognor Blakefest in 2019—it was fairly fleeting, as on most other occasions, an affectionate half-hug or light part on one another’s shoulders, and polite exchange of words. A softly spoken Irishman, there was something unassuming about him when one spoke to him up close, which seemed in contrast to his always impressive performance persona.

Niall was a poet who really did live poetry, not only through his prolific readings and performances, but also through the posthumous poetries of those he most admired and championed: Blake, Swedenborg, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Swinburne, W.B. Yeats, David Gascoyne, John Ashbery. Niall was also a champion of close poet-compatriots Heathcote Williams, Michael Horovitz, and Jeremy Reed.

It’s heartening to reflect on the wide and diverse dissemination of Niall’s poetry through numerous imprints and auspices: Waterloo Press (for his debut collection b/w), the aforementioned International Times, the avantgarde New River Press (Firing Slits: Jerusalem Colportage) and Ragged Lion Press (Free Poetry Series #1. Albion), the prestigious Blackwell’s Poetry series (No. 1), articles and poems in the Morning Star, The London Magazine, and many other journals, even History Today (a fascinating scholarly piece on Blake and Thomas Paine), and his engrossing blogsite Poetopography. In many ways dissemination via pamphlet was fitting for Niall’s spirit of colportage, as well as suiting his innate anti-establishment and anarchist sensibilities.

Niall had a prodigious track record of radio appearances, video documentaries (a significant archive on Youtube), and street theatre—having performed alongside such luminaries as Ken Campbell, Michael Horovitz, Iain Sinclair and Yoko Ono. Had the Free and Independent Republic of Frestonia (1977-80)—of which his late associate Heathcote Williams had been Ambassador—retained its sovereignty into Niall’s time in London, he would undoubtedly have been its poet laureate.

There were aspects of the poètemaudit to Niall but his gregarious Muse kept him at the centre of a community of poets, writers and artists. Niall’s trademark chalk-striped suits always seemed a sartorially ironic anti-complement to his demonstrable bohemianism but then they were often combined with gold-coloured trainers.

An irreplaceable presence in contemporary literary culture, Niall’s spirit will live on through his exceptional poetry, his prodigious contribution to a countercultural poetry narrative, and in the certainty that there will be many of us who will wish to ensure his legacy is kept alive just as he helped keep alive the posthumous reputations of so many past poets and writers.

Niall is survived by his mother Frances, his brother Roddy, his sister Yvonne, his partner Julie, and her son Heathcote.

Alan Morrison

Niall McDevitt’s new and final collection, London Nation, is now available from New River Press (www.thenewriverpress.com) in November.

This obituary has previously appeared on The Recusant, and in the Morning Star 11 Oct 2022.

Chipshop and Battlefield

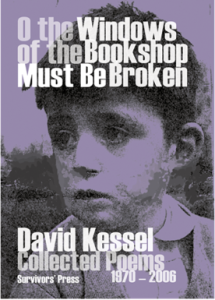

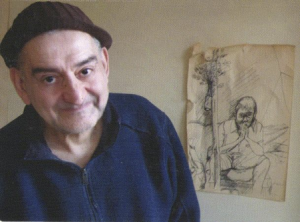

R.I.P. David Kessel

(10thApril 1947 – 8thMarch 2022)

Socialist poet and mental health activist

It is with deep sadness that I write of the death of lifelong poet and mental health activist David Kessel who passed away earlier this month (March, 2022) aged 74. I feel privileged to have known David, a deeply compassionateman, and greatly gifted poet, whose sheer humility was an example to us all in the poetry community. David was much loved, as was evidenced in a 2012 anthology of poems, Ravaged Wonderful Earth – A Collection for David Kessel, produced by Outsider Poets and Friends of East End Loonies (F.E.E.L.), two groups of which David was a promiment and—up until this time—active member.Indeed, he had penned a number of radical and thought-provoking pocket polemics on mental health and psychiatry which he used to distribute as small leaflets, often inserted in the folds of his spidery handwritten letters. These often read like speculative manifestoes.

The paranoid schizophrenia from which David suffered all his adult life, and for which he was heavily medicated (his speech became increasingly slurred as a result), never dimmed his empathic humanitarianism nor his ruminative mind which often expressed itself in aphorism. One that springs to mind is ‘Schizophrenia could be a diabetes of the mind’. David also strongly identified with the poets of both world wars, because he was a poet pitted in his own psychical war; for these reasons, and in terms of his poetic style, David most closely recalled Ivor Gurney.For example, David’s ‘Listening to the soft rain on the leaves/ I hear the decency and realism/ of friends’ humour’ has a similar cadence and comradely sentimentas Gurney’s ‘Who for his hours of life had chattered through/ Infinite lovely chatter of Bucks accent’.

But Davidalso had similarities with Isaac Rosenberg: while Rosenberg was the son of a Russian-Jewish immigrantwho settled in London’s East End, David was the grandson of a tailor ofGerman-Jewish ancestry (‘kessel’ is German for ‘kettle’) who emigrated from SouthAfrica to North London. By bizarre contrast his distaff grandfather had been a‘Blackshirt’ and poet.Indeed, David was open to the possibility that such a stark clash of ancestral qualities could have played some part in his schizophrenia. This posesan intriguing genetic theory on the illness, and David was ever the self-analyst (as in his essay The Utopianism of the Schizophrenic). His mother, an IrishCatholic and Communist, presumably had some influence on David’s politicsand poetics.